Jesse Eisenberg had a lot of things to factor into his performance as Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network, the least of which was Mark Zuckerberg. Regardless of how closely hewn the fictional character is from its real-life counterpart, Eisenberg has crafted something for the ages. He's the self-made man who realizes too late (if you can call 26 "too late") all that he's lost. But it cuts deeper than the Jay Gatsby archetype. Eisenberg manages to convey obliviousness and self-awareness in equal measure; something that's characteristic of most twenty-somethings today. We bathe ourselves in ironies and yet very often miss what's signified.

Now in his 80s, Hal Holbrook is turning in some of the best performances of his six-decade-long career. First in 2007's "Into the Wild," last year in That Evening Sun and very likely (if the adaptation takes its cues from the novel's treatment of his character) in this year's "Water for Elephants." As Abner Meecham, Holbrook tackles a lot of weighty issues, from grief to obsolescence to the onset of senility, with grace. He paints a full picture of a man full of rage, regret and remorse. It would be easy to feel one way or the other about Abner, but Holbrook always keeps it in the grey.

Teruyuki Kagawa's performance in Tokyo Sonata feels so unlike a performance, that it's easy to miss how well he communicates the weariness of laid off office drone Ryūhei. So much of his character is wrapped up in body language. How the man carries himself reveals a great deal about his mental state, indeed, far more than the platitudes and lies that leave his lips. He also has an amazing sense of timing. Kurosawa uses physical humor — watch how Ryūhei picks himself up out of the gutter — to lighten what could've been an overwhelmingly melancholy story. Kagawa is more than up for the challenge.

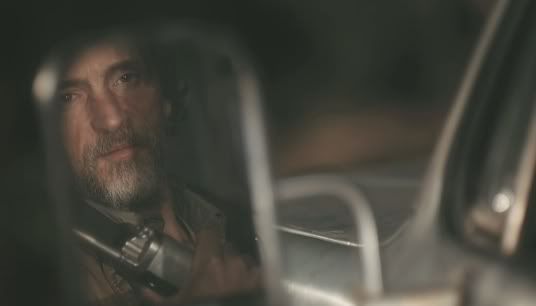

The evolution of Malik from a vulnerable Arab convict to a mob don is at first inexplicable. It's only after the film is over that it dawns on you how far he's come. Tahar Rahim handles that transition — which is integral to A Prophet — beautifully, instilling a quiet intelligence in his character. Malik, and Rahim, know not to let one hand know what the other is doing. At the same time, Rahim lets the audience in enough that the character remains sympathetic amidst his brutality and cunning.

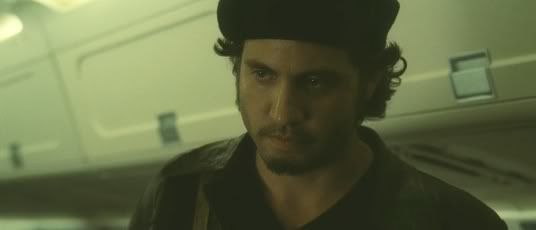

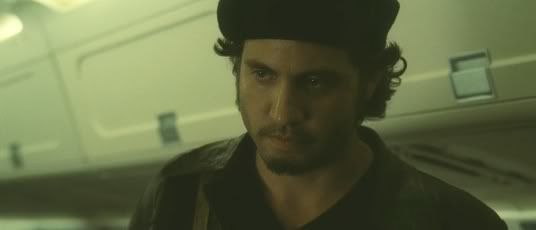

Édgar Ramírez's Carlos the Jackal is a consummate professional. Olivier Assayas' epic take on the terrorist/freedom fighter doesn't definitively answer the question of his loyalties, but one thing is clear from Ramírez's tightly-controlled performance. Carlos' first priority is himself. It's the through line in the performance, from a young, quick-witted charmer to an cruel, old has-been. Ramírez has to balance a lot of changes over the course of the film, but his focus is never lost.

Credit is also due Kim Yoon-seok who brings honesty and humor to his role as a pimp chasing down the serial killer who's been targeting his hookers in The Chaser. Alexander Siddig turns in a sensitive performance as Patricia Clarkson's escort-turned-love interest in Cairo Time. Once again, Song Kang-ho manages to be both charming and creepy as Jeon Do-yeon's unlikely lighthouse through the storm of Secret Sunshine.