And here they are: my favorite performances and technical achievements of the year. Click on the images for the full-write ups. The nominees are presented in list format at the bottom of this post with a slightly amended (including one addition and one upgrade) Top 20 from the one I started out with.

The Top Twenty Films of 2010

20. "Cairo Time" (Canada, dir. Ruba Nadda)

19. "Black Swan" (USA, dir. Darren Aronofsky)

18. "Toy Story 3" (USA, dir. Lee Unkrich)

17. "Salt" (USA, dir. Phillip Noyce)

16. “The Fighter” (USA, dir. David O. Russell)

15. "Inception" (USA, dir. Christopher Nolan)

14. "The Chaser" (South Korea, dir. Na Hong-jin)

13. "Night Catches Us" (USA, dir. Tanya Hamilton)

12. "True Grit" (USA, dir. Joel and Ethan Coen)

11. "Splice" (Canada, dir. Vincenzo Natali)

10. "I Am Love" (Italy, dir. Luca Guadagnino)

9. "Restrepo" (USA, dir. Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger)

8. "Animal Kingdom" (Australia, dir. David Michôd)

7. "A Prophet" (France, dir. Jacques Audiard)

6. "That Evening Sun" (USA, dir. Scott Teems)

5. "Secret Sunshine" (South Korea, dir. Lee Chang-dong)

4. "Enter the Void" (France/Germany/Italy, dir. Gaspar Noé)

3. "Tokyo Sonata" (Japan, dir. Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

2. "Mother" (South Korea, dir. Bong Joon-ho)

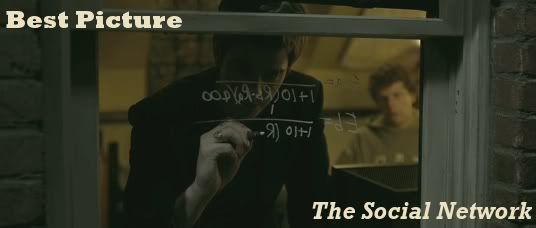

1. "The Social Network" (USA, dir. David Fincher)

Best Director

Bong Joon-ho (Mother)

David Fincher (The Social Network)

Luca Guadagnino (I Am Love)

Kiyoshi Kurosawa (Tokyo Sonata)

Gaspar Noé (Enter the Void)

Best Actor

Jesse Eisenberg (The Social Network)

Hal Holbrook (That Evening Sun)

Teruyuki Kagawa (Tokyo Sonata)

Tahar Rahim (A Prophet)

Édgar Ramírez (Carlos)

Best Actress

Jeon Do-yeon (Secret Sunshine)

Kim Hye-ja (Mother)

Jennifer Lawrence (Winter's Bone)

Natalie Portman (Black Swan)

Tilda Swinton (I Am Love)

Best Supporting Actor

Neils Arestrup (A Prophet)

Christian Bale (The Fighter)

Michael Fassbender (Fish Tank)

John Hawkes (Winter's Bone)

Ray McKinnon (That Evening Sun)

Best Supporting Actress

Melissa Leo (The Fighter)

Carrie Preston (That Evening Sun)

Charlotte Rampling (Life During Wartime)

Hailee Steinfeld (True Grit)

Jacki Weaver (Animal Kingdom)

Best Ensemble Performance

Shirley Henderson, Allison Janney, Ally Sheedy, Ciarán Hinds, Dylan Riley Snyder, Michael Lerner, Charlotte Rampling, Michael K. Williams, Paul Reubens, Rich Pecci (Life During Wartime)

Hal Holbrook, Raymond McKinnon, Carrie Preston, Mia Wasikowska, Walton Goggins, Barry Corbin, Dixie Carter (That Evening Sun)

Katie Jarvis, Kierston Wareing, Michael Fassbender and Rebecca Griffiths (Fish Tank)

Teruyuki Kagawa, Kyôko Koizumi, Yû Koyanagi, Kai Inowaki, Haruka Igawa and Kanji Tsuda (Tokyo Sonata)

Anthony Mackie, Kerry Washington, Jamara Griffin, Wendell Pierce, Jamie Hector and Amari Cheatom (Night Catches Us)

Best Original Screenplay

Bong Joon-ho and Park Eun-kyo (Mother)

Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Max Mannix and Sachiko Tanaka (Tokyo Sonata)

David Michôd (Animal Kingdom)

Vincenzo Natali, Antoinette Terry Bryant and Doug Taylor (Splice)

Todd Solondz (Life During Wartime)

Best Adapted Screenplay

Joel and Ethan Coen (True Grit)

Peter Craig, Ben Affleck and Aaron Stockard (The Town)

John Curran (The Killer Inside Me)

Aaron Sorkin (The Social Network)

Scott Teems (That Evening Sun)

Best Cinematography

Jeff Cronenweth (The Social Network)

Benoît Debie (Enter the Void)

Hong Kyeong-pyo (Mother)

Yorick Le Saux (I Am Love)

Martin Ruhe (The American)

Best Editing

Stuart Baird and John Gilroy (Salt)

Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall (The Social Network)

Marc Boucrot and Gaspar Noé (Enter the Void)

Lee Smith (Inception)

Juliette Welfling (A Prophet)

Best Art Direction

Roshelle Berliner and Matteo De Cosmo (Life During Wartime)

Thérèse DePrez, David Stein and Tora Peterson (Black Swan)

Guy Dyas, Frank Walsh and Larry Dias (Agora)

Jess Gonchor, Christina Ann Wilson and Nancy Haigh (True Grit)

Albrecht Konrad, David Scheunemann and Bernhard Henrich (The Ghost Writer)

Best Musical Score

John Adams (I Am Love)

Lee Byung-woo (Mother)

Clint Mansell (Black Swan)

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (The Social Network)

Hans Zimmer (Inception)

Best Sound Design

~ Enter the Void

~ Inception

~ The Social Network

Best Visual Effects

~ Enter the Void

~ Inception

~ The Social Network